Tutorial

How To Create a Web Server in Node.js with the HTTP Module

The author selected the COVID-19 Relief Fund to receive a donation as part of the Write for DOnations program.

Introduction

When you view a webpage in your browser, you are making a request to another computer on the internet, which then provides you the webpage as a response. That computer you are talking to via the internet is a web server. A web server receives HTTP requests from a client, like your browser, and provides an HTTP response, like an HTML page or JSON from an API.

A lot of software is involved for a server to return a webpage. This software generally falls into two categories: frontend and backend. Front-end code is concerned with how the content is presented, such as the color of a navigation bar and the text styling. Back-end code is concerned with how data is exchanged, processed, and stored. Code that handles network requests from your browser or communicates with the database is primarily managed by back-end code.

Node.js allows developers to use JavaScript to write back-end code, even though traditionally it was used in the browser to write front-end code. Having both the frontend and backend together like this reduces the effort it takes to make a web server, which is a major reason why Node.js is a popular choice for writing back-end code.

In this tutorial, you will learn how to build web servers using the http module that’s included in Node.js. You will build web servers that can return JSON data, CSV files, and HTML web pages.

Simplify deploying Node.js applications with DigitalOcean App Platform. Deploy Node directly from GitHub in minutes.

Prerequisites

- Ensure that Node.js is installed on your development machine. This tutorial uses Node.js version 10.19.0. To install this on macOS or Ubuntu 18.04, follow the steps in How to Install Node.js and Create a Local Development Environment on macOS or the Installing Using a PPA section of How To Install Node.js on Ubuntu 18.04.

- The Node.js platform supports creating web servers out of the box. To get started, be sure you’re familiar with the basics of Node.js. You can get started by reviewing our guide on How To Write and Run Your First Program in Node.js.

- We also make use of asynchronous programming for one of our sections. If you’re not familiar with asynchronous programming in Node.js or the

fsmodule for interacting with files, you can learn more with our article on How To Write Asynchronous Code in Node.js.

Step 1 — Creating a Basic HTTP Server

Let’s start by creating a server that returns plain text to the user. This will cover the key concepts required to set up a server, which will provide the foundation necessary to return more complex data formats like JSON.

First, we need to set up an accessible coding environment to do our exercises, as well as the others in the article. In the terminal, create a folder called first-servers:

- mkdir first-servers

Then enter that folder:

- cd first-servers

Now, create the file that will house the code:

- touch hello.js

Open the file in a text editor. We will use nano as it’s available in the terminal:

- nano hello.js

We start by loading the http module that’s standard with all Node.js installations. Add the following line to hello.js:

const http = require("http");

The http module contains the function to create the server, which we will see later on. If you would like to learn more about modules in Node.js, check out our How To Create a Node.js Module article.

Our next step will be to define two constants, the host and port that our server will be bound to:

...

const host = 'localhost';

const port = 8000;

As mentioned before, web servers accept requests from browsers and other clients. We may interact with a web server by entering a domain name, which is translated to an IP address by a DNS server. An IP address is a unique sequence of numbers that identify a machine on a network, like the internet. For more information on domain name concepts, take a look at our An Introduction to DNS Terminology, Components, and Concepts article.

The value localhost is a special private address that computers use to refer to themselves. It’s typically the equivalent of the internal IP address 127.0.0.1 and it’s only available to the local computer, not to any local networks we’ve joined or to the internet.

The port is a number that servers use as an endpoint or “door” to our IP address. In our example, we will use port 8000 for our web server. Ports 8080 and 8000 are typically used as default ports in development, and in most cases developers will use them rather than other ports for HTTP servers.

When we bind our server to this host and port, we will be able to reach our server by visiting http://localhost:8000 in a local browser.

Let’s add a special function, which in Node.js we call a request listener. This function is meant to handle an incoming HTTP request and return an HTTP response. This function must have two arguments, a request object and a response object. The request object captures all the data of the HTTP request that’s coming in. The response object is used to return HTTP responses for the server.

We want our first server to return this message whenever someone accesses it: "My first server!".

Let’s add that function next:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.writeHead(200);

res.end("My first server!");

};

The function would usually be named based on what it does. For example, if we created a request listener function to return a list of books, we would likely name it listBooks(). Since this one is a sample case, we will use the generic name requestListener.

All request listener functions in Node.js accept two arguments: req and res (we can name them differently if we want). The HTTP request the user sends is captured in a Request object, which corresponds to the first argument, req. The HTTP response that we return to the user is formed by interacting with the Response object in second argument, res.

The first line res.writeHead(200); sets the HTTP status code of the response. HTTP status codes indicate how well an HTTP request was handled by the server. In this case, the status code 200 corresponds to "OK". If you are interested in learning about the various HTTP codes that your web servers can return with the meaning they signify, our guide on How To Troubleshoot Common HTTP Error Codes is a good place to start.

The next line of the function, res.end("My first server!");, writes the HTTP response back to the client who requested it. This function returns any data the server has to return. In this case, it’s returning text data.

Finally, we can now create our server and make use of our request listener:

...

const server = http.createServer(requestListener);

server.listen(port, host, () => {

console.log(`Server is running on http://${host}:${port}`);

});

Save and exit nano by pressing CTRL+X.

In the first line, we create a new server object via the http module’s createServer() function. This server accepts HTTP requests and passes them on to our requestListener() function.

After we create our server, we must bind it to a network address. We do that with the server.listen() method. It accepts three arguments: port, host, and a callback function that fires when the server begins to listen.

All of these arguments are optional, but it is a good idea to explicitly state which port and host we want a web server to use. When deploying web servers to different environments, knowing the port and host it is running on is required to set up load balancing or a DNS alias.

The callback function logs a message to our console so we can know when the server began listening to connections.

Note: Even though requestListener() does not use the req object, it must still be the first argument of the function.

With less than fifteen lines of code, we now have a web server. Let’s see it in action and test it end-to-end by running the program:

- node hello.js

In the console, we will see this output:

OutputServer is running on http://localhost:8000

Notice that the prompt disappears. This is because a Node.js server is a long running process. It only exits if it encounters an error that causes it to crash and quit, or if we stop the Node.js process running the server.

In a separate terminal window, we’ll communicate with the server using cURL, a CLI tool to transfer data to and from a network. Enter the command to make an HTTP GET request to our running server:

- curl http://localhost:8000

When we press ENTER, our terminal will show the following output:

OutputMy first server!

We’ve now set up a server and got our first server response.

Let’s break down what happened when we tested our server. Using cURL, we sent a GET request to the server at http://localhost:8000. Our Node.js server listened to connections from that address. The server passed that request to the requestListener() function. The function returned text data with the status code 200. The server then sent that response back to cURL, which displayed the message in our terminal.

Before we continue, let’s exit our running server by pressing CTRL+C. This interrupts our server’s execution, bringing us back to the command line prompt.

In most web sites we visit or APIs we use, the server responses are seldom in plain text. We get HTML pages and JSON data as common response formats. In the next step, we will learn how to return HTTP responses in common data formats we encounter in the web.

Step 2 — Returning Different Types of Content

The response we return from a web server can take a variety of formats. JSON and HTML were mentioned before, and we can also return other text formats like XML and CSV. Finally, web servers can return non-text data like PDFs, zipped files, audio, and video.

In this article, in addition to the plain text we just returned, you’ll learn how to return the following types of data:

- JSON

- CSV

- HTML

The three data types are all text-based, and are popular formats for delivering content on the web. Many server-side development languages and tools have support for returning these different data types. In the context of Node.js, we need to do two things:

- Set the

Content-Typeheader in our HTTP responses with the appropriate value. - Ensure that

res.end()gets the data in the right format.

Let’s see this in action with some examples. The code we will be writing in this section and later ones have many similarities to the code we wrote previously. Most changes exist within the requestListener() function. Let’s create files with this “template code” to make future sections easier to follow.

Create a new file called html.js. This file will be used later to return HTML text in an HTTP response. We’ll put the template code here and copy it to the other servers that return various types.

In the terminal, enter the following:

- touch html.js

Now open this file in a text editor:

- nano html.js

Let’s copy the “template code.” Enter this in nano:

const http = require("http");

const host = 'localhost';

const port = 8000;

const requestListener = function (req, res) {};

const server = http.createServer(requestListener);

server.listen(port, host, () => {

console.log(`Server is running on http://${host}:${port}`);

});

Save and exit html.js with CTRL+X, then return to the terminal.

Now let’s copy this file into two new files. The first file will be to return CSV data in the HTTP response:

- cp html.js csv.js

The second file will return a JSON response in the server:

- cp html.js json.js

The remaining files will be for later exercises:

- cp html.js htmlFile.js

- cp html.js routes.js

We’re now set up to continue our exercises. Let’s begin with returning JSON.

Serving JSON

JavaScript Object Notation, commonly referred to as JSON, is a text-based data exchange format. As its name suggests, it is derived from JavaScript objects, but it is language independent, meaning it can be used by any programming language that can parse its syntax.

JSON is commonly used by APIs to accept and return data. Its popularity is due to lower data transfer size than previous data exchange standards like XML, as well as the tooling that exists that allow programs to parse them without excessive effort. If you’d like to learn more about JSON, you can read our guide on How To Work with JSON in JavaScript.

Open the json.js file with nano:

- nano json.js

We want to return a JSON response. Let’s modify the requestListener() function to return the appropriate header all JSON responses have by changing the highlighted lines like so:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

};

...

The res.setHeader() method adds an HTTP header to the response. HTTP headers are additional information that can be attached to a request or a response. The res.setHeader() method takes two arguments: the header’s name and its value.

The Content-Type header is used to indicate the format of the data, also known as media type, that’s being sent with the request or response. In this case our Content-Type is application/json.

Now, let’s return JSON content to the user. Modify json.js so it looks like this:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(`{"message": "This is a JSON response"}`);

};

...

Like before, we tell the user that their request was successful by returning a status code of 200. This time in the response.end() call, our string argument contains valid JSON.

Save and exit json.js by pressing CTRL+X. Now, let’s run the server with the node command:

- node json.js

In another terminal, let’s reach the server by using cURL:

- curl http://localhost:8000

As we press ENTER, we will see the following result:

Output{"message": "This is a JSON response"}

We now have successfully returned a JSON response, just like many of the popular APIs we create apps with. Be sure to exit the running server with CTRL+C so we can return to the standard terminal prompt. Next, let’s look at another popular format of returning data: CSV.

Serving CSV

The Comma Separated Values (CSV) file format is a text standard that’s commonly used for providing tabular data. In most cases, each row is separated by a newline, and each item in the row is separated by a comma.

In our workspace, open the csv.js file with a text editor:

- nano csv.js

Let’s add the following lines to our requestListener() function:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/csv");

res.setHeader("Content-Disposition", "attachment;filename=oceanpals.csv");

};

...

This time, our Content-Type indicates that a CSV file is being returned as the value is text/csv. The second header we add is Content-Disposition. This header tells the browser how to display the data, particularly in the browser or as a separate file.

When we return CSV responses, most modern browsers automatically download the file even if the Content-Disposition header is not set. However, when returning a CSV file we should still add this header as it allows us to set the name of the CSV file. In this case, we signal to the browser that this CSV file is an attachment and should be downloaded. We then tell the browser that the file’s name is oceanpals.csv.

Let’s write the CSV data in the HTTP response:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/csv");

res.setHeader("Content-Disposition", "attachment;filename=oceanpals.csv");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(`id,name,email\n1,Sammy Shark,shark@ocean.com`);

};

...

Like before we return a 200/OK status with our response. This time, our call to res.end() has a string that’s a valid CSV. The comma separates the value in each column and the new line character (\n) separates the rows. We have two rows, one for the table header and one for the data.

We’ll test this server in the browser. Save csv.js and exit the editor with CTRL+X.

Run the server with the Node.js command:

- node csv.js

In another Terminal, let’s reach the server by using cURL:

- curl http://localhost:8000

The console will show this:

Outputid,name,email

1,Sammy Shark,shark@ocean.com

If we go to http://localhost:8000 in our browser, a CSV file will be downloaded. Its file name will be oceanpals.csv.

Exit the running server with CTRL+C to return to the standard terminal prompt.

Having returned JSON and CSV, we’ve covered two cases that are popular for APIs. Let’s move on to how we return data for websites people view in a browser.

Serving HTML

HTML, HyperText Markup Language, is the most common format to use when we want users to interact with our server via a web browser. It was created to structure web content. Web browsers are built to display HTML content, as well as any styles we add with CSS, another front-end web technology that allows us to change the aesthetics of our websites.

Let’s reopen html.js with our text editor:

- nano html.js

Modify the requestListener() function to return the appropriate Content-Type header for an HTML response:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

};

...

Now, let’s return HTML content to the user. Add the highlighted lines to html.js so it looks like this:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(`<html><body><h1>This is HTML</h1></body></html>`);

};

...

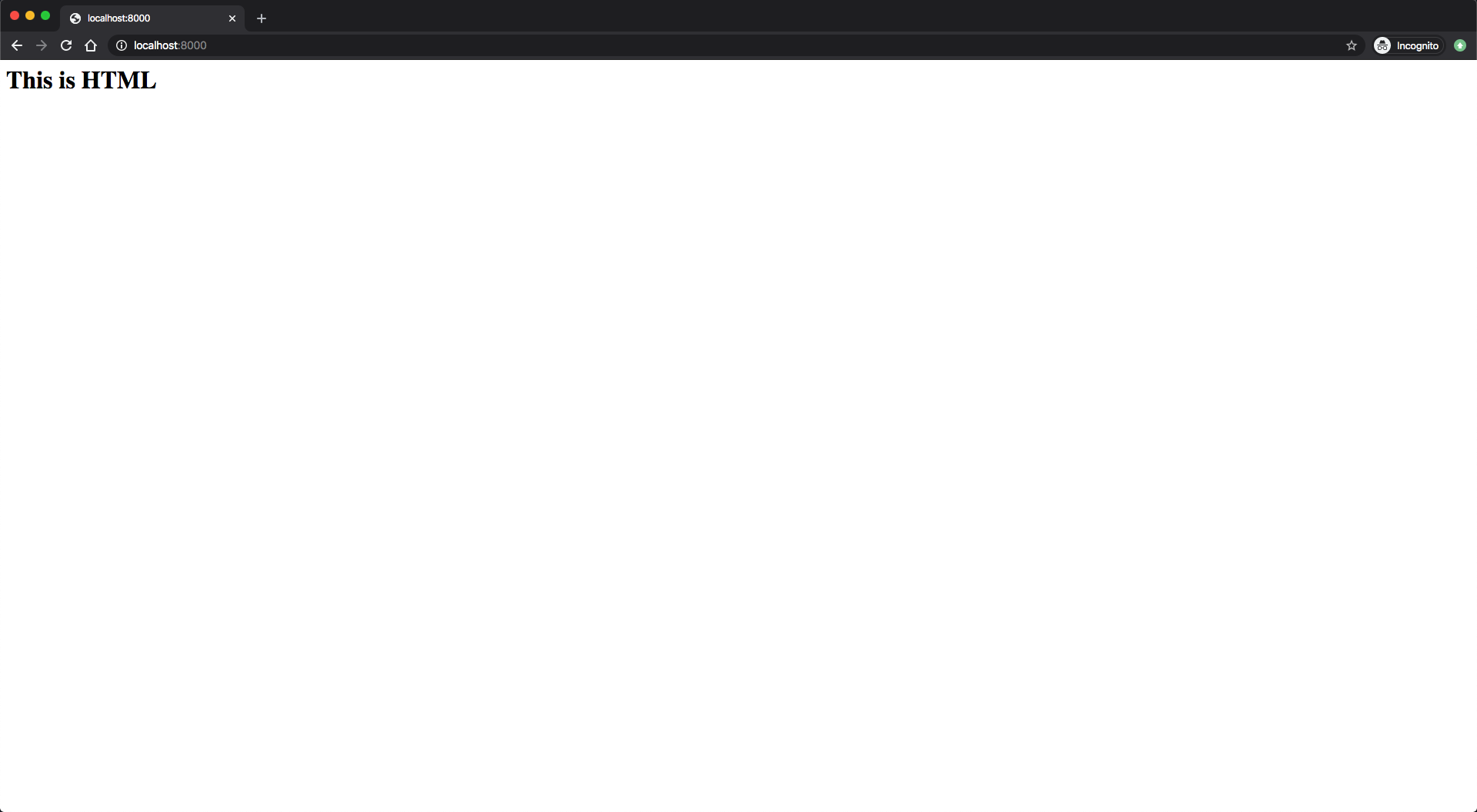

We first add the HTTP status code. We then call response.end() with a string argument that contains valid HTML. When we access our server in the browser, we will see an HTML page with one header tag containing This is HTML.

Let’s save and exit by pressing CTRL+X. Now, let’s run the server with the node command:

- node html.js

We will see Server is running on http://localhost:8000 when our program has started.

Now go into the browser and visit http://localhost:8000. Our page will look like this:

Let’s quit the running server with CTRL+C and return to the standard terminal prompt.

It’s common for HTML to be written in a file, separate from the server-side code like our Node.js programs. Next, let’s see how we can return HTML responses from files.

Step 3 — Serving an HTML Page From a File

We can serve HTML as strings in Node.js to the user, but it’s preferable that we load HTML files and serve their content. This way, as the HTML file grows we don’t have to maintain long strings in our Node.js code, keeping it more concise and allowing us to work on each aspect of our website independently. This “separation of concerns” is common in many web development setups, so it’s good to know how to load HTML files to support it in Node.js

To serve HTML files, we load the HTML file with the fs module and use its data when writing our HTTP response.

First, we’ll create an HTML file that the web server will return. Create a new HTML file:

- touch index.html

Now open index.html in a text editor:

- nano index.html

Our web page will be minimal. It will have an orange background and will display some greeting text in the center. Add this code to the file:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<head>

<title>My Website</title>

<style>

*,

html {

margin: 0;

padding: 0;

border: 0;

}

html {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

body {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

position: relative;

background-color: rgb(236, 152, 42);

}

.center {

width: 100%;

height: 50%;

margin: 0;

position: absolute;

top: 50%;

left: 50%;

transform: translate(-50%, -50%);

color: white;

font-family: "Trebuchet MS", Helvetica, sans-serif;

text-align: center;

}

h1 {

font-size: 144px;

}

p {

font-size: 64px;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

<div class="center">

<h1>Hello Again!</h1>

<p>This is served from a file</p>

</div>

</body>

</html>

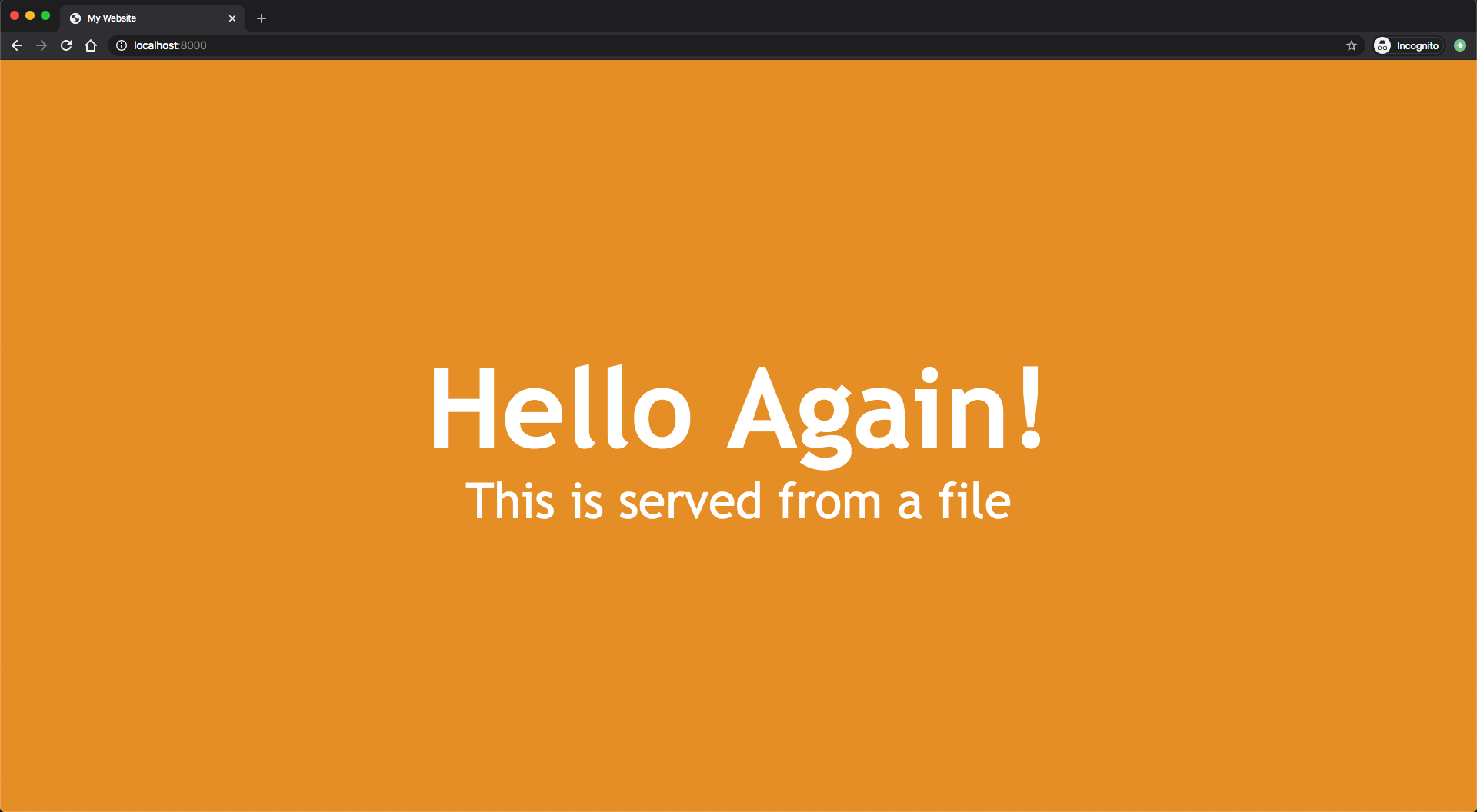

This single webpage shows two lines of text: Hello Again! and This is served from a file. The lines appear in the center of the page, one above each other. The first line of text is displayed in a heading, meaning it would be large. The second line of text will appear slightly smaller. All the text will appear white and the webpage has an orange background.

While it’s not the scope of this article or series, if you are interested in learning more about HTML, CSS, and other front-end web technologies, you can take a look at Mozilla’s Getting Started with the Web guide.

That’s all we need for the HTML, so save and exit the file with CTRL+X. We can now move on to the server code.

For this exercise, we’ll work on htmlFile.js. Open it with the text editor:

- nano htmlFile.js

As we have to read a file, let’s begin by importing the fs module:

const http = require("http");

const fs = require('fs').promises;

...

This module contains a readFile() function that we’ll use to load the HTML file in place. We import the promise variant in keeping with modern JavaScript best practices. We use promises as its syntactically more succinct than callbacks, which we would have to use if we assigned fs to just require('fs'). To learn more about asynchronous programming best practices, you can read our How To Write Asynchronous Code in Node.js guide.

We want our HTML file to be read when a user requests our system. Let’s begin by modifying requestListener() to read the file:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

fs.readFile(__dirname + "/index.html")

};

...

We use the fs.readFile() method to load the file. Its argument has __dirname + "/index.html". The special variable __dirname has the absolute path of where the Node.js code is being run. We then append /index.html so we can load the HTML file we created earlier.

Now let’s return the HTML page once it’s loaded:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

fs.readFile(__dirname + "/index.html")

.then(contents => {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(contents);

})

};

...

If the fs.readFile() promise successfully resolves, it will return its data. We use the then() method to handle this case. The contents parameter contains the HTML file’s data.

We first set the Content-Type header to text/html to tell the client that we are returning HTML data. We then write the status code to indicate the request was successful. We finally send the client the HTML page we loaded, with the data in the contents variable.

The fs.readFile() method can fail at times, so we should handle this case when we get an error. Add this to the requestListener() function:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

fs.readFile(__dirname + "/index.html")

.then(contents => {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(contents);

})

.catch(err => {

res.writeHead(500);

res.end(err);

return;

});

};

...

Save the file and exit nano with CTRL+X.

When a promise encounters an error, it is rejected. We handle that case with the catch() method. It accepts the error that fs.readFile() returns, sets the status code to 500 signifying that an internal error was encountered, and returns the error to the user.

Run our server with the node command:

- node htmlFile.js

In the web browser, visit http://localhost:8000. You will see this page:

You have now returned an HTML page from the server to the user. You can quit the running server with CTRL+C. You will see the terminal prompt return when you do.

When writing code like this in production, you may not want to load an HTML page every time you get an HTTP request. While this HTML page is roughly 800 bytes in size, more complex websites can be megabytes in size. Large files can take a while to load. If your site is expecting a lot of traffic, it may be best to load HTML files at startup and save their contents. After they are loaded, you can set up the server and make it listen to requests on an address.

To demonstrate this method, let’s see how we can rework our server to be more efficient and scalable.

Serving HTML Efficiently

Instead of loading the HTML for every request, in this step we will load it once at the beginning. The request will return the data we loaded at startup.

In the terminal, re-open the Node.js script with a text editor:

- nano htmlFile.js

Let’s begin by adding a new variable before we create the requestListener() function:

...

let indexFile;

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

...

When we run this program, this variable will hold the HTML file’s contents.

Now, let’s readjust the requestListener() function. Instead of loading the file, it will now return the contents of indexFile:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "text/html");

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(indexFile);

};

...

Next, we shift the file reading logic from the requestListener() function to our server startup. Make the following changes as we create the server:

...

const server = http.createServer(requestListener);

fs.readFile(__dirname + "/index.html")

.then(contents => {

indexFile = contents;

server.listen(port, host, () => {

console.log(`Server is running on http://${host}:${port}`);

});

})

.catch(err => {

console.error(`Could not read index.html file: ${err}`);

process.exit(1);

});

Save the file and exit nano with CTRL+X.

The code that reads the file is similar to what we wrote in our first attempt. However, when we successfully read the file we now save the contents to our global indexFile variable. We then start the server with the listen() method. The key thing is that the file is loaded before the server is run. This way, the requestListener() function will be sure to return an HTML page, as indexFile is no longer an empty variable.

Our error handler has changed as well. If the file can’t be loaded, we capture the error and print it to our console. We then exit the Node.js program with the exit() function without starting the server. This way we can see why the file reading failed, address the problem, and then start the server again.

We’ve now created different web servers that return various types of data to a user. So far, we have not used any request data to determine what should be returned. We’ll need to use request data when setting up different routes or paths in a Node.js server, so next let’s see how they work together.

Step 4 — Managing Routes Using an HTTP Request Object

Most websites we visit or APIs we use usually have more than one endpoint so we can access various resources. A good example would be a book management system, one that might be used in a library. It would not only need to manage book data, but it would also manage author data for cataloguing and searching convenience.

Even though the data for books and authors are related, they are two different objects. In these cases, software developers usually code each object on different endpoints as a way to indicate to the API user what kind of data they are interacting with.

Let’s create a new server for a small library, which will return two different types of data. If the user goes to our server’s address at /books, they will receive a list of books in JSON. If they go to /authors, they will receive a list of author information in JSON.

So far, we have been returning the same response to every request we get. Let’s illustrate this quickly.

Re-run our JSON response example:

- node json.js

In another terminal, let’s do a cURL request like before:

- curl http://localhost:8000

You will see:

Output{"message": "This is a JSON response"}

Now let’s try another curl command:

- curl http://localhost:8000/todos

After pressing Enter, you will see the same result:

Output{"message": "This is a JSON response"}

We have not built any special logic in our requestListener() function to handle a request whose URL contains /todos, so Node.js returns the same JSON message by default.

As we want to build a miniature library management server, we’ll now separate the kind of data that’s returned based on the endpoint the user accesses.

First, exit the running server with CTRL+C.

Now open routes.js in your text editor:

- nano routes.js

Let’s begin by storing our JSON data in variables before the requestListener() function:

...

const books = JSON.stringify([

{ title: "The Alchemist", author: "Paulo Coelho", year: 1988 },

{ title: "The Prophet", author: "Kahlil Gibran", year: 1923 }

]);

const authors = JSON.stringify([

{ name: "Paulo Coelho", countryOfBirth: "Brazil", yearOfBirth: 1947 },

{ name: "Kahlil Gibran", countryOfBirth: "Lebanon", yearOfBirth: 1883 }

]);

...

The books variable is a string that contains JSON for an array of book objects. Each book has a title or name, an author, and the year it was published.

The authors variable is a string that contains the JSON for an array of author objects. Each author has a name, a country of birth, and their year of birth.

Now that we have the data our responses will return, let’s start modifying the requestListener() function to return them to the correct routes.

First, we’ll ensure that every response from our server has the correct Content-Type header:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

}

...

Now, we want to return the right JSON depending on the URL path the user visits. Let’s create a switch statement on the request’s URL:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

switch (req.url) {}

}

...

To get the URL path from a request object, we need to access its url property. We can now add cases to the switch statement to return the appropriate JSON.

JavaScript’s switch statement provides a way to control what code is run depending on the value of an object or JavaScript expression (for example, the result of mathematical operations). If you need a lesson or reminder on how to use them, take a look at our guide on How To Use the Switch Statement in JavaScript.

Let’s continue by adding a case for when the user wants to get our list of books:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

switch (req.url) {

case "/books":

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(books);

break

}

}

...

We set our status code to 200 to indicate the request is fine and return the JSON containing the list of our books. Now let’s add another case for our authors:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

switch (req.url) {

case "/books":

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(books);

break

case "/authors":

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(authors);

break

}

}

...

Like before, the status code will be 200 as the request is fine. This time we return the JSON containing the list of our authors.

We want to return an error if the user tries to go to any other path. Let’s add the default case to do this:

...

const requestListener = function (req, res) {

res.setHeader("Content-Type", "application/json");

switch (req.url) {

case "/books":

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(books);

break

case "/authors":

res.writeHead(200);

res.end(authors);

break

default:

res.writeHead(404);

res.end(JSON.stringify({error:"Resource not found"}));

}

}

...

We use the default keyword in a switch statement to capture all other scenarios not captured by our previous cases. We set the status code to 404 to indicate that the URL they were looking for was not found. We then set a JSON object that contains an error message.

Let’s test our server to see if it behaves as we expect. In another terminal, let’s first run a command to see if we get back our list of books:

- curl http://localhost:8000/books

Press Enter to see the following output:

Output[{"title":"The Alchemist","author":"Paulo Coelho","year":1988},{"title":"The Prophet","author":"Kahlil Gibran","year":1923}]

So far so good. Let’s try the same for /authors. Type the following command in the terminal:

- curl http://localhost:8000/authors

You will see the following output when the command is complete:

Output[{"name":"Paulo Coelho","countryOfBirth":"Brazil","yearOfBirth":1947},{"name":"Kahlil Gibran","countryOfBirth":"Lebanon","yearOfBirth":1883}]

Last, let’s try an erroneous URL to ensure that requestListener() returns the error response:

- curl http://localhost:8000/notreal

Entering that command will display this message:

Output{"error":"Resource not found"}

You can exit the running server with CTRL+C.

We’ve now created different avenues for users to get different data. We also added a default response that returns an HTTP error if the user enters a URL that we don’t support.

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you’ve made a series of Node.js HTTP servers. You first returned a basic textual response. You then went on to return various types of data from our server: JSON, CSV, and HTML. From there you were able to combine file loading with HTTP responses to return an HTML page from the server to the user, and to create an API that used information about the user’s request to determine what data should be sent in its response.

You’re now equipped to create web servers that can handle a variety of requests and responses. With this knowledge, you can make a server that returns many HTML pages to the user at different endpoints. You could also create your own API.

To learn about more HTTP web servers in Node.js, you can read the Node.js documentation on the http module. If you’d like to continue learning Node.js, you can return to the How To Code in Node.js series page.

DigitalOcean provides multiple options for deploying Node.js applications, from our simple, affordable virtual machines to our fully-managed App Platform offering. Easily host your Node.js application on DigitalOcean in seconds.

Tutorial Series: How To Code in Node.js

Node.js is a popular open-source runtime environment that can execute JavaScript outside of the browser. The Node runtime is commonly used for back-end web development, leveraging its asynchronous capabilities to create networking applications and web servers. Node also is a popular choice for building command line tools.

In this series, you will go through exercises to learn the basics of how to code in Node.js, gaining powerful tools for back-end and full stack development in the process.

This textbox defaults to using Markdown to format your answer.

You can type !ref in this text area to quickly search our full set of tutorials, documentation & marketplace offerings and insert the link!

Featured on Community

Get our biweekly newsletter

Sign up for Infrastructure as a Newsletter.

Hollie's Hub for Good

Working on improving health and education, reducing inequality, and spurring economic growth? We'd like to help.

Become a contributor

Get paid to write technical tutorials and select a tech-focused charity to receive a matching donation.

Thanks very much for this article. Your explanations accompanying each step are invaluable. Really enjoyed this tutorial!

Just wonderful … thank you, both!

well explained! it is very helpful.